11 August 2022

Rainwater Harvesting Around the World – Maldives

In 2014, a drinking water crisis occurred in the capital of the honeymoon islands, and residents of the main island of Male were left with inadequate tap water supplies after a fire at a desalination plant.

Male being one of the most densely populated capitals of the world, more than a third of the population was left without water for drinking, bathing, cooking, and cleaning.

The small island state was in a state of emergency requiring immediate international assistance. Mounting anger of the residents triggered unrest on the streets to force the then-President of the Maldives, Abdulla Yameen to tackle this unfolding water crisis.

Drinking water shortage on the outer islands during the dry season significantly impacted people’s health, food security and productivity. Groundwater contamination and poor sanitation exacerbated the risk of water-borne diseases and other infections.

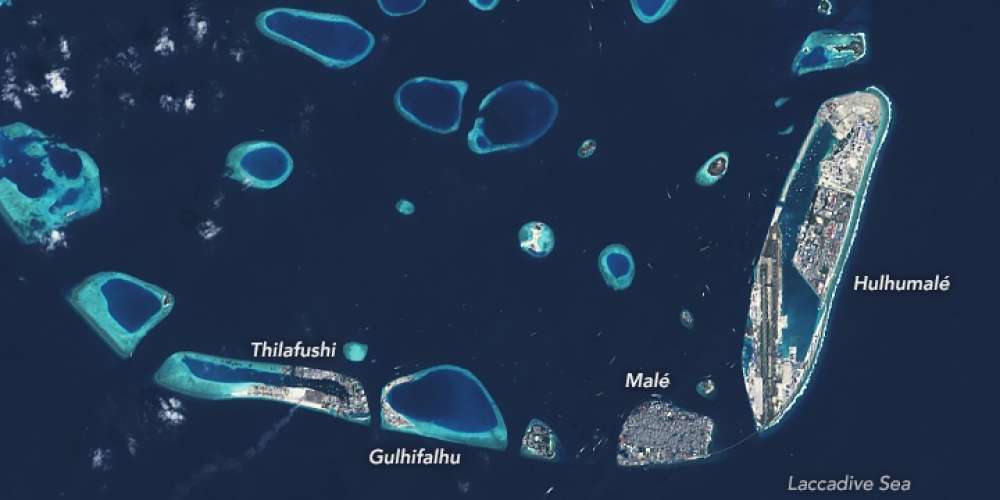

The situation was only being exacerbated by increasingly unpredictable rainfall and sea level rise, which strengthened the importance of ongoing action on climate change. With more than 80 per cent of its 1,190 coral islands standing less than 1 meter above sea level, the Maldives is extremely vulnerable to climate change. In addition, existing human-driven pressure on the natural environment made the storm worse. Recognising the scale of the challenges, the Maldivian government made ‘adaptation’ a top national priority and focused on climate action.

In 2017, an integrated water resources management programme (IWRM), initially established by the Adaptation Fund, was steered with the backing of the Green Climate Fund and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The $28.2 million project worked alongside the Ministry of Environment to secure safe, reliable, and uninterrupted year-round water supply to residents of the most vulnerable outer islands.

Adaptation Fund’s project proposal recorded that 77% of Maldivians relied on rainwater for drinking in 2010. Hence a scheme was rolled out to redesign and improve the harvesting of this water. Even with some delays due to COVID-19 travel restrictions and supply chain issues, the project is now in its final stages where seventeen Rainwater Harvesting Systems have already been completed. The new systems use ultrafiltration to treat harvested rainwater and are designed to collect 150,000 litres of water (in addition to water collected at various public buildings), which is a great improvement on existing community systems. Taken together, the Rainwater Harvesting Systems are expected to store some 3,750,000L of water to provide an uninterrupted supply of clean water for 25 communities (around 20,000 people).

The project pursued three primary methods including the harvesting of rainwater, the implantation of water recharge systems and the desalination of seawater. A concept of hybrid water production technology successfully combined seawater desalination technology with rainwater collection, which blends into a singular water production and delivery system which brought the project innovative success.

Maldives Meteorological Service has been working closely with the project and has handed over Six Automatic Weather Stations to support climate-related data collection. This has enhanced weather forecasting as well as more accurate rainfall predictions and enabled improved rainwater harvesting. The Water and Sanitation Department also continuously monitor and analyse groundwater conditions using a new geographic information system (GIS). A popular weather app in the Maldives, Moosun has been updated where 43,000+ of its users can receive location-based notifications on rainfall probability and volume in a particular area.

The project has also specifically influenced legislation mandating water production within the country to be fully powered via renewable sources. This not only adds to the country’s carbon-neutral ambition but also reduces its dependency on fuel imports for its water security. The project represents a turning point in water security in the Maldives, marking a move away from reactive emergency measures to longer-term solutions, with benefits on all fronts.

Importantly, the cost-effective project’s model makes it more affordable for households and the state, as well as cuts down the cost of imported fuel by switching to renewable energy. The decentralization of water production and distribution allows communities to now have access to water in a more timely way during emergency situations. The cost of water supply during dry periods is estimated to be cut down by 40 per cent, which means an annual saving of around US$98,000 (MVR 1.5 million). Due to the scalability and efficiency of the model, the Ministry of National Planning, Housing and Infrastructure has now fully adopted it to install necessary infrastructure across the other atolls and islands.

The project has leveraged more than US$333 million in public funds for further scaling to help meet the government’s pledge to provide water networks for all inhabited islands by 2023. With access to safe drinking water, communities will be able to see improved social security, reduced health concerns, and less migration from outer islands. It will also benefit the development of local tourism, and livelihoods, making annual water shortages a thing of the past.